The notion of a Network of PsychoLogical Domains has evolved out of the concept of ‘logical levels’ as used in NLP and originates from the work of Gregory Bateson. Bateson’s ideas were inspired by philosopher Bertrand Russell’s work on logic.

Bateson defines mind as processes of transformation that disclose a hierarchy of logical types immanent in the phenomena. To understand how something works or what purpose it serves, requires making distinctions within the wholeness of our experience. If we are simply immersed in our senses in the present passing moment we aren’t sorting for patterns. By framing our attention in various ways we are able to make distinctions not otherwise available. For example, viewing events over an extended timeframe enables us to see the self-perpetuating nature of particular behaviors. Or by observing a situation while framing it in comparison to how we would ideally like it to be, we highlight what could be done differently to improve it. There are many perceptual frameworks that (for the most part unconsciously) shape the way we perceive, give meaning to and relate to life.

Levels of Learning

Theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman’s[i] proposed three levels of evolution, with evolution being synonymous with learning, and if we add ‘not evolving or not learning’ to we have four levels of learning. What he referred to as ‘rule-based behavior’ — in which there is no trial and error and therefore no learning — we simply maintain the status quo within that environment.

This level of relating to the environment approximates nonliving systems. The first level of evolution, we learn from trial and error, is to improve the way we relate to other elements in our environment. This necessitates and, as well, precipitates other people evolving the way they relate to us. It is coevolution. These types of changes often create new niches that invite innovation. This coevolution evolves further when we learn how to learn better. To examine how we learn requires a much different way of framing our perception than acting by rote or even learning through trial and error.

The next level of learning is that of epistemology, which basically means, the study of ‘how’ we know what (we think) we know. In other words how we learn to learn what we learn. Each level is a further abstraction from the physicality of our experience until we are actually examining the nature of perception. In meditation we see a similar pattern in observing the nature of mind, as contrasted with observing the objects of our perception, the objects of our thinking or the interaction of the objects of our thinking.

An example of these four levels of learning can be seen in marriage. A couple in homeostasis is basically behaving by rote. They have developed automatic behavior patterns and with a certain feeling of, ‘this is as good as it gets’, neither party is are thinking about how they can learn from their experience to improve their marriage. If, however, one or both of them begins to feel dissatisfied, for whatever reason, then they begin to pay attention to what is causing the problems. They might even experiment with ways of approaching things differently. This might lead to new ways of communicating — in particular talking about the ways to improve their relationship. It may include not just talking about what they can change, but discussing how they can improve they way they address problems and look for solutions. In the process of trying to improve the way they go about solving problems they become even more aware of how each of them perceive and think about things very differently. Some of these ways of thinking seem to help them solve problems; others keep them going in circles.

A very sophisticated couple might be able to help one another to explore how they know what they think they know, or this might be when they approach a therapist. To observe the way the mind thinks means being able to observe these processes from a perspective outside of the processes that make the perceptions in the first place.

A skilled therapist can show a person how to observe the workings of their mind well enough to identify the processes of making the meanings and beliefs that shape perception and behavior. Therapy with mindfulness meditation methods could help them develop awareness of how their minds manufacture perception and make beliefs.

Behavior, Capabilities, Beliefs and Values, and Identity

Bateson described four levels of learning in terms of ‘behavior’, ‘capabilities’, ‘beliefs and values’, and ‘identity’. At the first level we can simply behave without learning. At the second level, through trial and error, we more fully use our capabilities to improve the quality of our behavior. At the third level we can ask what is the purpose of using particular capabilities to behave in a particular way. How we learn and what we choose to learn is determined by what we value and believe. At the fourth level the way we decide what to value and believe and to maintain those values and beliefs is often thought of as being simply who we are. Our style of thinking and feeling defines our personality, which is why when someone is first asked how they know what they know or how they know what they want, they say, “It’s just who I am.”

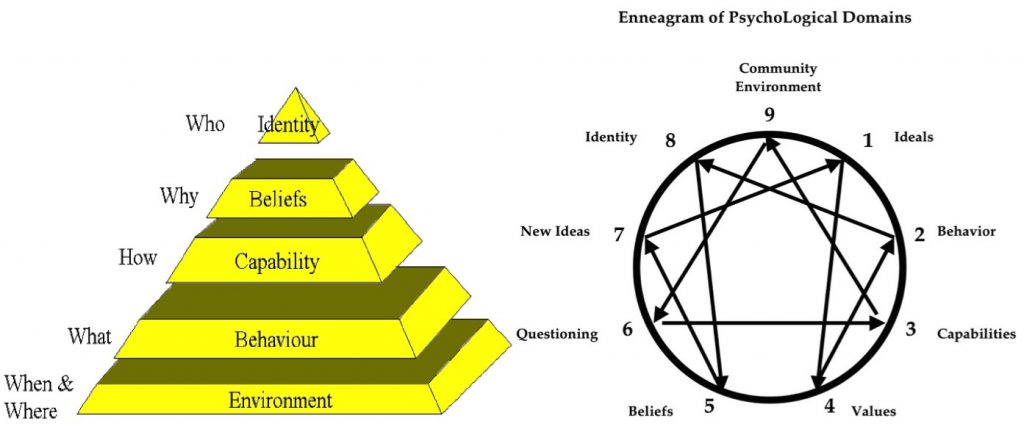

NLP innovator, Robert Dilts, refined Bateson’s model by adding ‘spiritual’ and ‘environmental’ levels. Any behavior happens in an environment and the different environments will determine what will or won’t occur. Having a transpersonal perspective of oneself is often thought of as a ‘spiritual’ experience. Dilts’ model has proven useful in facilitating change but it is flawed, theoretically (I will attempt to address the flaws with the essential wholeness model). First of all he describes these definitional categories in a hierarchy, one stacked upon the other, with ‘environment’ at the bottom and ‘spirituality’ at the top. Each category is supposedly a member of the categories above it. However, ‘environment’ is not a member of the category of ‘behavior’, ‘behavior’ is a subset of capabilities, but is not a ‘value’ or ‘belief’. The problem occurs when trying to place these useful distinctions into a linear hierarchical model, when life is better understood — as Fritjof Capra described it — as “networks nesting within other networks”. Since application of these principles requires some linear sequence of behavior the hierarchical model can be useful, but we must not confuse the map with the territory. Transferring the model to the circular representation of the Enneagram with its internal lines of connection creates a model that more closely resembles the network-like structure of a living system.

At each phase in the developmental cycle there is a tendency for us to organize, or frame, our cognitions into one of these categories. However, since they are merely artificial distinctions within the wholeness of our experience, they are always available for us to frame our experience. It is also important to remember that words such as ‘behavior’, ‘values’, ‘beliefs’ and ‘identity’ are nominalizations. That is, concepts created from verbs or actions. They are not actually things; rather they are processes (behaving, valuing, believing, identifying), ways of constructing perception and are, by nature, fluid and changing. For these reasons we will refer to the categories as ‘PsychoLogical Networks’.

Each number on the Enneagram, in conjunction with representing a phase in the process of change, also represents a corresponding PsychoLogical Network. Dilts’ list of logical levels is expanded to nine domains (including community) mapped out around the circle. The Spiritual or Being level is represented by the Enneagram symbol as a whole. According to Bateson’s model of logical types it would appear that ideals should be part of the category including beliefs and values.

Differentiating Types of Knowing

The Enneagram helps us differentiate beliefs and values into five categories ranging from values at FOUR, beliefs at FIVE, new ideas at SEVEN, identity at EIGHT and ideals at ONE. The model shows us that at ONE — Ideals is connected to FOUR — Values and SEVEN — new ideas. And FIVE — beliefs are connected to EIGHT––identity and SEVEN––new ideas.

It is important to understand how values inform ideals and, somehow, ideals are organized by and help organize new ideas. In addition, personal identity and the beliefs and values one identifies with are largely shaped and informed by the communities to which we belong or are born into. We could think of community in a sense as a cultural context (or environment). That is why these two distinctions are both located at NINE on the Enneagram.

An overview of this expanded model shows us that our evolving life occurs in a particular environment and we have a network of associations that define what happens in that environment. Whether we are conscious of them or not, there is a network of ideals (platonic ideas) that define the optimal events in that environment. To move in the direction of those ideals specific behaviors must be performed. In order to behave in those specific ways we must have specific capabilities that we engage. Whether we use those capabilities depends on what we value. What we value is organized by what we most deeply believe. What we believe has been organized by our questioning of what is true, important and useful. We question what we believe because of the new ideas and perceptions we become aware of. The structure of our personal identity organizes our awareness of ideas, how we question, believe, value and how we are capable of behaving in moving towards an ideal in any environmental context. The communities to which we belong tend to organize the way we identify ourselves.

Each PsychoLogical domain acts as an attractor basin of possible ways of framing our experience. The smaller the volume of basin the more limited our perception. As consciousness evolves the volume of the basins expands to more global or universal frameworks. The perceptual framework of each psychological domain facilitates the achieving of the developmental task of the corresponding phase of the developmental cycle.

For a complete cycle of change to occur, there must be potential for something new to emerge at each level. New growth and learning is informed by self-organizing morphic fields, but must be implemented in ways that the best options can be selected, and those evolve towards their potential.

So for our homeostatic patterns in any environment or context to be perturbed enough to break habitual patterns there must be a compelling ideal to motivate one to attempt new behaviors, which require developing latent or emerging capabilities, which is in part supported by existing values and beliefs, but also restrained. In order to have a change to a higher or more complex order these existing values and beliefs must be questioned and at least in part let go of in order for new ideas to emerge and be appreciated. Putting new ideas into practice allows a new sense of identity to be recognized. That identity will then seek to see how it fits within existing communities or become part of, or even create a new sense of community.

David’s Story

Let’s consider this process by examining David’s crisis. For whatever reasons, David believes that he’s the kind of person that people dislike. He thinks that whatever he does in relation to others will be unappreciated and disapproved. He also feels unable to cope with this disapproval and, after even the briefest interactions, usually feels rejected and hurt. To cope with this, he tries to convince himself that he doesn’t care what others think and that he doesn’t need people in his life. He works as a bookkeeper for a warehousing and distribution company. For the most part he can avoid contact with people by staying in his isolated office and keeping his nose in the books and computer. Everyone who has contact with him has largely given up trying to talk with him. They rarely converse beyond the minimum exchange needed to conduct business. Because David’s discomfort with personal contact is so apparent and he is so awkward to deal with, most people communicate through notes and email. David, on one hand likes the space, but interprets people avoiding him as evidence that people don’t want to have anything to do with him.

David lives by himself and has set routines of where he shops for food and other activities, which also minimizes his contact with others. He has learned, increasingly over time, to disregard and repress any internal thoughts or feelings that would challenge this pattern of thinking and relating. Day-to-day, month-to-month, year-to-year, his life has little change. However, recently his employer has been finding more simple mistakes in his bookkeeping. David interprets this as his boss just not liking him and being out to get him. Out of a growing sense of resentment towards the company, David begins to feel justified in stealing small amounts of petty cash. He knows he is jeopardizing his job and security, but can’t help himself. As he’s afraid to raise suspicion he truncates any contact with fellow employees. His behavior has, however, the opposite effect, as his boss notices this change and suggests that he talk to the employee assistance counselor. David denies any problem and argues he is doing his job well and should be left alone. This isn’t good enough for the boss who tells him if things don’t change he will be forced to consider laying David off. This sends David into a crisis. His job has been the main focus of his life, he feels overwhelmed by the idea of being unemployed or having to look for a new job. He decides his only option is to see the counselor. Out of desperation he continues to see the counselor long enough to establish the kind of rapport that means he can begin freeing himself from the rigid ideas and perceptions that have controlled his life.

The therapist helps David to not only to question his old belief about being disliked by others but also to entertain and experiment with the idea that there are people who will like him, once given the chance to get to know him. So, instead of becoming more limited and lifeless, pattern of his life reverses and begins to open up to wider circles of interaction. He starts to think he is the kind of person people can get along with as he feels more a part of the workplace community and eventually even makes some friends outside work.

Personality Types

The Primary concern of each phase is the same primary concern or perceptual bias of people caught in the compulsion of their Enneagram personality type. Each of the nine personality types overly identifies with one phase of the evolutionary process and the PsychoLogical Domain and so resists the next phase. They fear losing the ground they have gained and so cling to what they are familiar with and do best. Compulsions of personality in this light are merely vicious cycles that keep them locked into a fraction of their wholeness while resisting the natural tendency to evolve over time.

People with type NINE personality become preoccupied with maintaining stability by surrendering their own agenda and ignore what is problematic for them and others. They tend to be overly identified with their environment or community.

People with type ONE personality become preoccupied with what’s problematic and resist making adaptations. They tend to be overly identified with their ideals.

People with type TWO personality become preoccupied with adapting their behavior and resist promoting their own agenda. They tend to be overly identified with their behavior.

People with type THREE personality become preoccupied with promoting their own agenda, but resist awareness of their own inadequacies. They tend to be overly identified their capabilities.

People with type FOUR personality become preoccupied with awareness of their own inadequacies and resist clarifying their assumptions. They tend to be overly identified with their values.

People with type FIVE personality become preoccupied with clarifying their assumptions and resist questioning these assumptions. They tend to be overly identified with their beliefs.

People with type SIX personality become preoccupied with questioning assumptions, but resist considering new possibilities. They tend to be overly identified with questioning.

People with type SEVEN personality become preoccupied with new possibilities, but resist reorganizing their lives. They tend to be overly identified with their new ideas.

People with type EIGHT personality become preoccupied with reorganizing circumstances and resist surrendering their personal agenda to help maintain greater stability and harmony in their relationships. They tend to be overly identified with their personal identity.

[i] Kauffman, Stuart, (1995) At Home in the Universe; The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity. New York: Oxford University Press,

For more read: Essential Wholeness, Integral Psychotherapy, Spiritual Awakening and the Enneagram